Original Research Published on December 26, 2025

Outcome of closure of Skull Base Defect after Endonasal Endoscopic Resection of Skull Base Tumours-

A Retrospective Longitudinal Study

Rajesh Raju George1, Sebil Mathai2, Gayathri Raju3

1. Senior Consultant & HOD, Rajagiri Hospital, Aluva, Kerala; 2.Fellow in Rhinology, Rajagiri Hospital, Aluva, Kerala; 3. Biostatistician, Department of Clinical epidemiology, Rajagiri hospital, Aluva*

Corresponding Author: Dr Sebil Mathai

Fellow in Rhinology, Rajagiri Hospital, Aluva

Email: sebilmathaithekkan@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Background: Effective closure of skull base defects is vital in preventing postoperative complications such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, infection, and structural herniation following endoscopic skull base surgery. This study aims to assess the clinical and radiological outcomes of skull base defect closure in patients who underwent endoscopic repair.

Methods: Fifty patients who underwent endoscopic skull base surgery for various benign pathologies were evaluated. Patient demographics, diagnosis,and postoperative findings (including flap uptake, crusting, nasal bleeding, CSF leak, and infection) were recorded. Follow-up assessments were done on the 3rd day, 3rd week, 3rd month, and 6th month postoperatively. Radiological assessment (CT scan) was performed on day 1 post-surgery and MRI scan at 6 months.

Results: The cohort had a mean age of 52.7±15.97 years; 34% were male and 66% female. The most common diagnosis was pituitary macroadenoma (72%). Flap uptake was 100% at all follow-up points with no flap rejections. Crusting peaked at the 3rd week (100%), decreased by the 3rd month (86%), and resolved in most cases by 6 months (14% persistence). Nasal bleeding was reported in 20% on the 3rd day, which declined to 4% by 6 months. No cases of postoperative CSF leak or infection were observed at any follow-up. CT imaging confirmed complete closure of the skull base defect in all patients, with no brain herniation and only one case of compression of optic nerve,with decrease in visual acuity where patient was taken to theatre and decompression done followed by reconstruction.

Conclusion: Endoscopic skull base defect closure demonstrates excellent clinical and radiological outcomes, with no postoperative CSF leaks or infections observed. Most cases of crusting and nasal bleeding resolved within 6 months. The employed repair technique is both safe and effective for the management of skull base pathologies

Keywords: Endoscopic skull base surgery, Pituitary adenoma, Clinical and radiological outcome, CSF leak, Crusting

Introduction

Skull base tumors can generally be classified as benign which includes meningiomas, sellar/parasellar tumors, vestibular and trigeminal schwannomas and malignant such as chordoma, chondrosarcoma, metastasis. The incidence of skull base meningiomas is 2 per 100,000 per year. The incidence of pituitary tumors and vestibular schwannomas is 1 per 100,000 per year. Skull base metastases are more common and have an incidence of 18 per 100,000 per year. Until the later decades of 20th century, lesions located at the base of the skull were considered inoperable. The introduction of microsurgical techniques, advances in neuroanesthesiology, magnetic resonance imaging, neuronavigation, endoscopy, high-speed drills, and hemostatic agents have dramatically changed the management of these tumors.1

The skull base is one of the most complex anatomic locations in the human body. It acts as a relay station for cranial nerves. Expansion of endoscopic endonasal approaches (EEA) has produced significant shift in the surgical management of skull base lesions. 2-surgeon, 2-nostril, 4-hands technique is followed in endoscopic endonasal skull base approaches.2

The paramedian skull base can be divided into anterior, middle, and posterior segments. EEAs to the anterior segment offer access to the intraconal orbital space and the optic canal. A transpterygoid corridor typically precedes EEAs to the middle and posterior paramedian approaches. EEAs to the middle segment provide wide exposure of the petrous apex, middle cranial fossa (including cavernous sinus and Meckel cave), infratemporal fossa and pterygopalatine fossa. Finally, EEAs to the posterior segment access the hypoglossal canal, occipital condyle, and jugular foramen.3

The endoscopic endonasal approach to the skull base provides a direct anatomical route to the lesion without traversing any major neurovascular structures and avoids brain retraction. Restricted working space and the danger of an inadequate dural repair with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage and potential for meningitis are some disadvantages this approach. Endoscopic endonasal approach often require a large opening of the dura mater over the tuberculum sellae and posterior planum sphenoidale, or retro clival space depending on extent of disease.This surgeries can also cause large intraoperative CSF leaks, which necessitate precise and effective dural closure.4

So in our study we will be discussing our experience with closure of skull base defect with multilayers and gasket closure in endoscopic endonasal skull base surgeries.

Aims and Objectives

Aims

To assess the reconstructed skull base defects after nasal endoscopic resection of skull base tumours

Objectives

Primary objective: Assess closure of skull base defect endoscopically on day 3, third week, third month and sixth month and by CT scan on day 1 postoperatively and MRI at 6 months.

Secondary objective: To identify the complications associated with the technique

Methods

This is a retrospective longitudinal study conducted in department of ENT Rajagiri Hospital, Aluva, Kerala from May 2025 on surgeries conducted. As per the study by Thorp D sample size was calculated as 50.The surgical technique involved multilayerd closure of skull base with duragen, fat, fascia lata with septal cartilage as gasket, nasoseptal flap and fixed with fibrin glue. Gelfoam placed over reconstructed materials. Nasal packing was done with merocele.

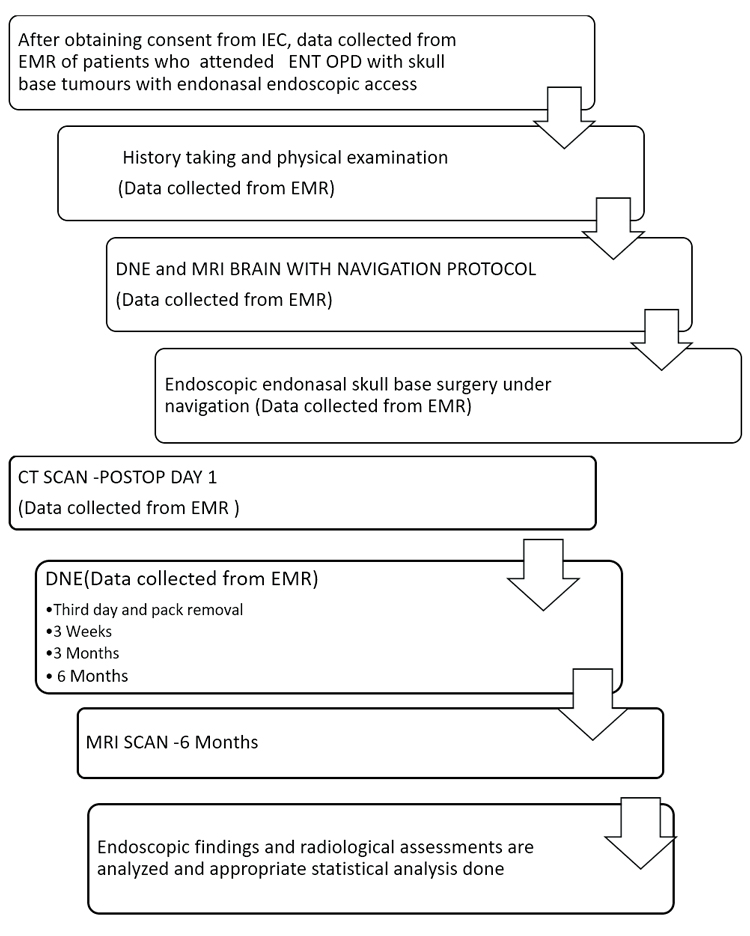

Brief procedure: (Flowchart 1)

Flow chart 1. Brief Procedure

Results

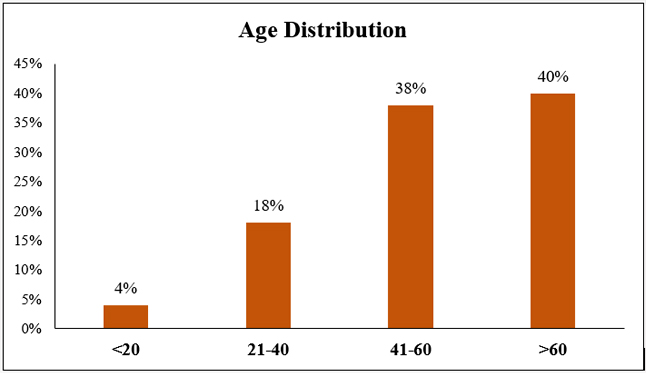

The figure 1 shows the population is predominantly older, with 78% aged above 40. The largest group is those over 60 (40%), while only 4% are under 20, indicating an aging demographic.

Figure 1. Bar Graph showing age distribution

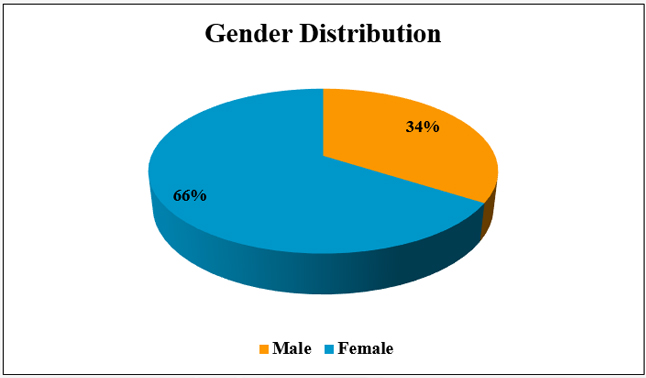

The pie chart (Figure 2) shows that females make up 66% and males comprise 34% of the population, indicating a higher representation of females.

Figure 2. Pie chart showing gender distribution

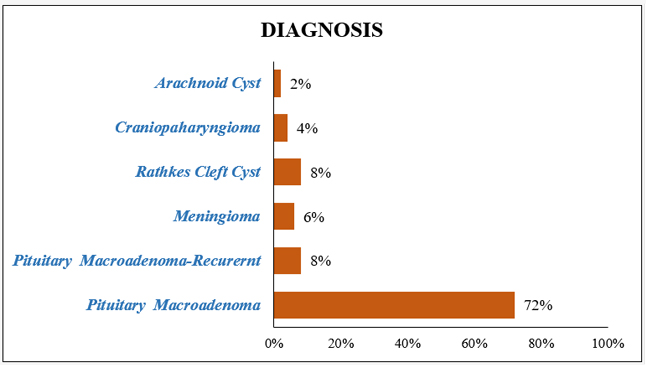

This figure 3 shows that Pituitary Macroadenoma is the most common diagnosis (72%), followed by Rathke’s Cleft Cyst and recurrent Pituitary Macroadenoma (8% each). Less common conditions include Meningioma (6%), Craniopharyngioma (4%), and Arachnoid Cyst (2%). Most cases involve pituitary-related tumors.

Figure 3. Bar Graph showing skull base pathology distribution

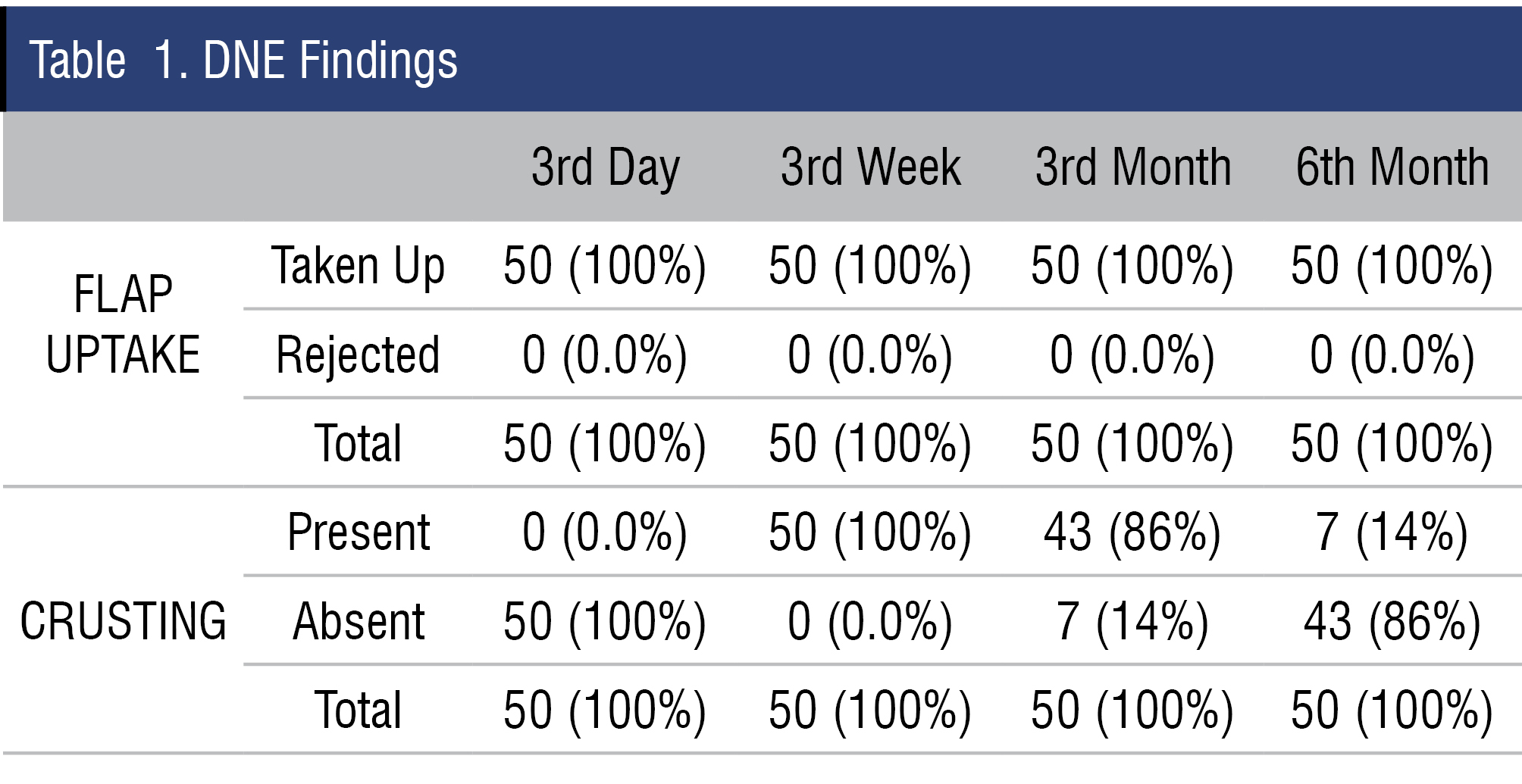

Table 1 shows that Flap uptake was 100% with no CSF leak or infection. Crusting peaked at 3 weeks and reduced by 6 months. Nasal bleeding was mild and decreased over time. Overall, outcomes were excellent.

Figure 4. Reconstructed Skull Base

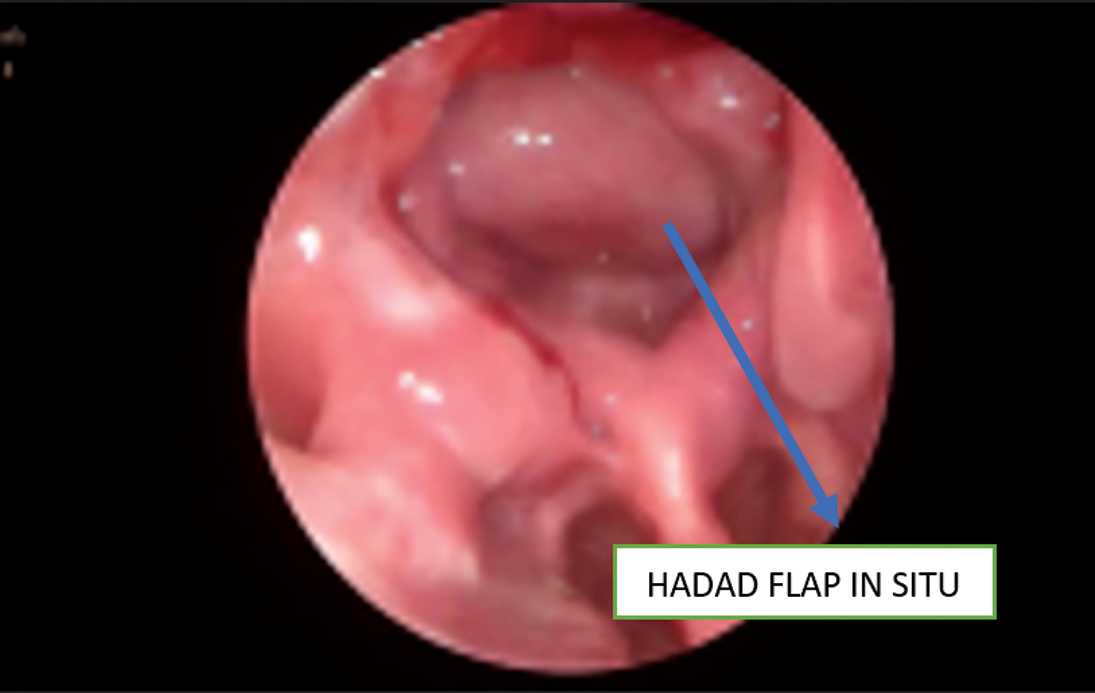

DNE FINDINGS: (6 months) (Figure 4)

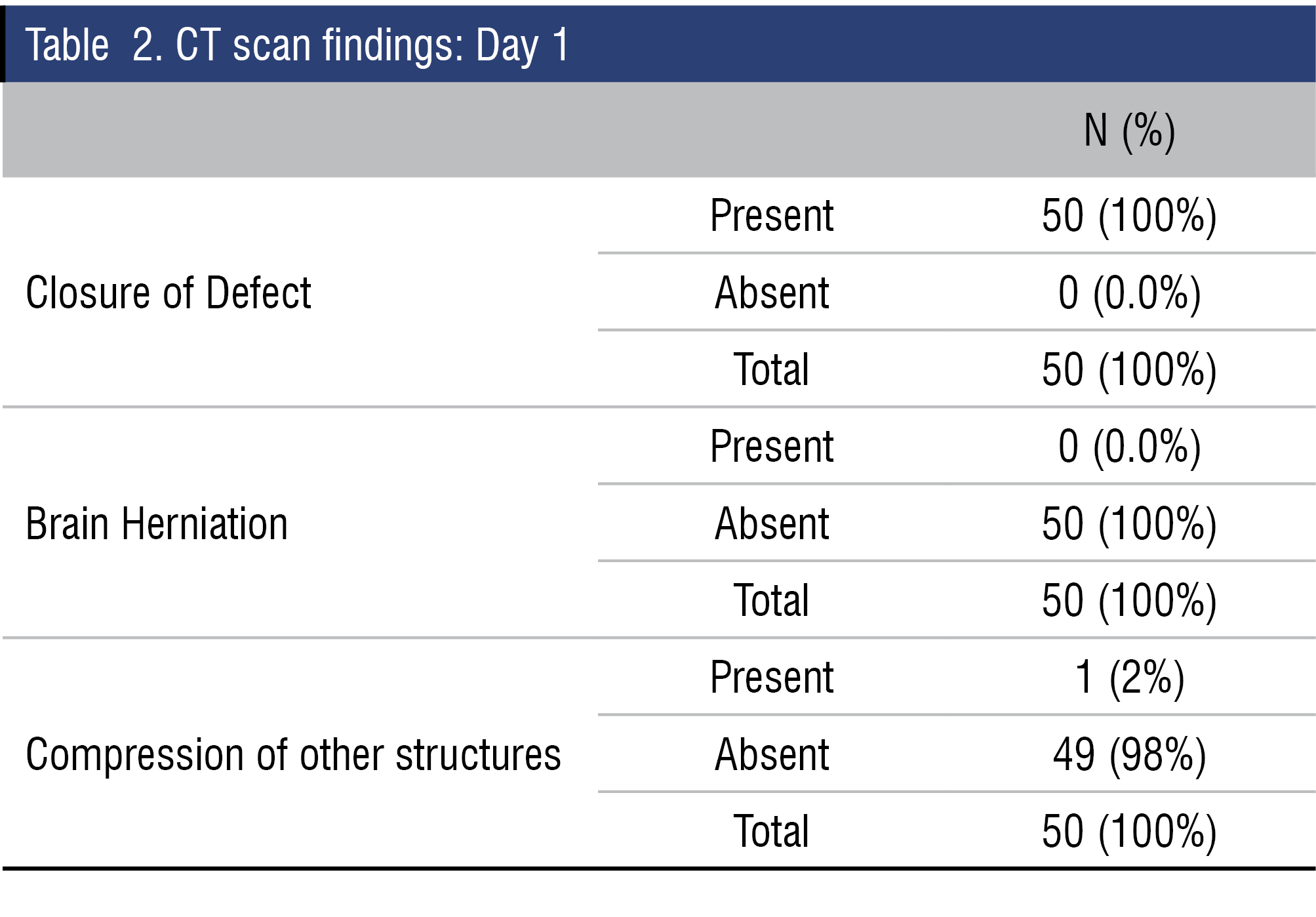

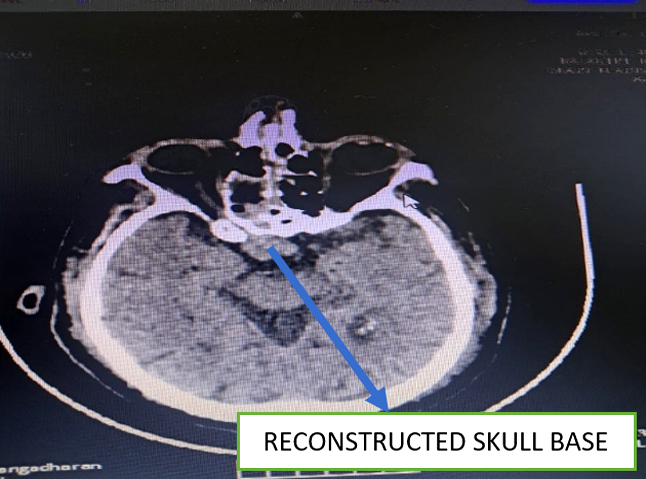

All 50 patients had successful defect closure (100%), with no cases of brain herniation. Only 1 patient (2%) showed compression of other structures, indicating a largely favorable early post-operative outcome.One patient had optic nerve compression by reconstructed materials which caused decrease in visual acuity.The patient was taken to operation theatre and release of compression and skull base reconstruction was done for the patient after which vision improved (Table 2 & Figure 5).

Figure 5. CT BRAIN - POSTOP DAY 1

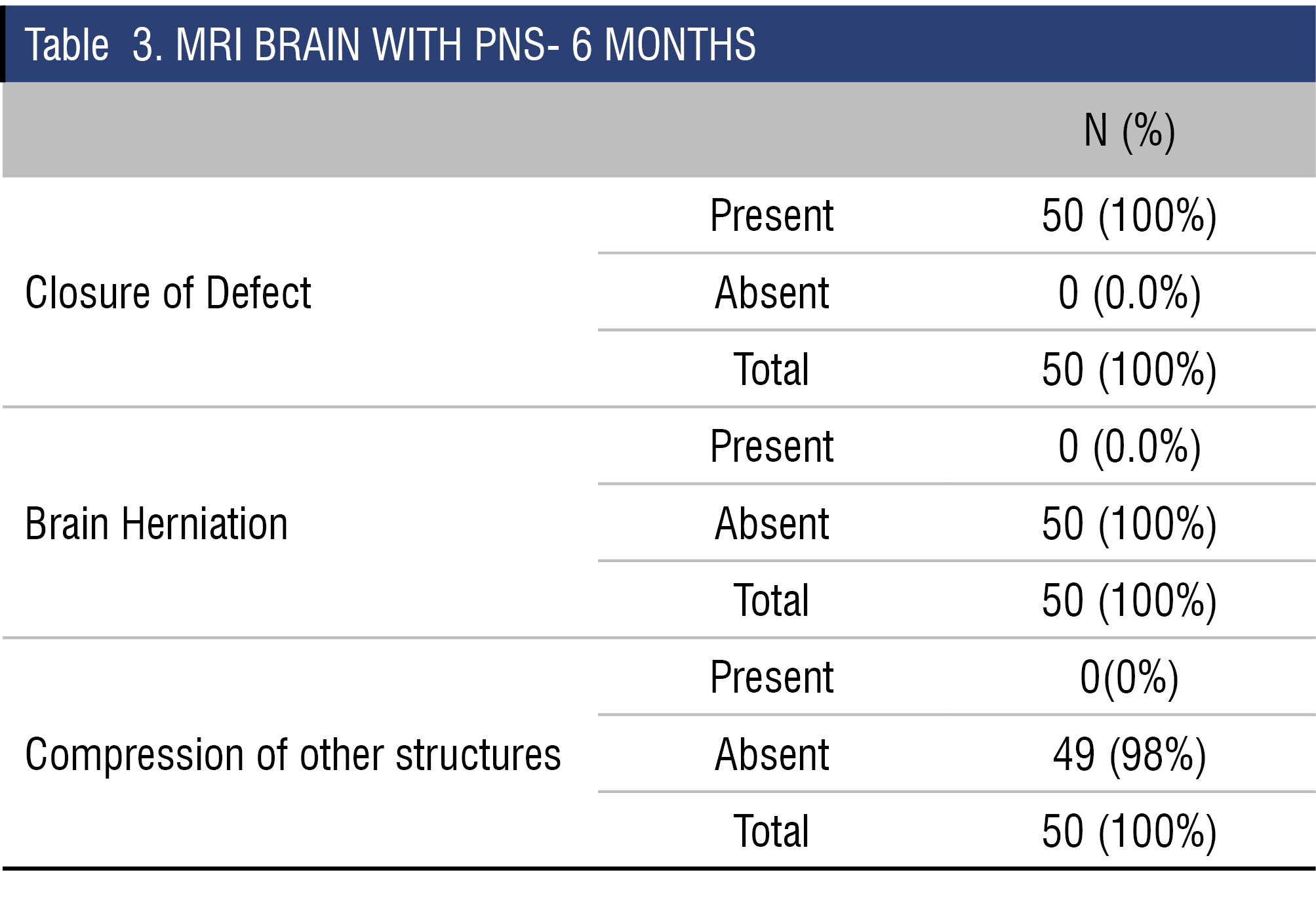

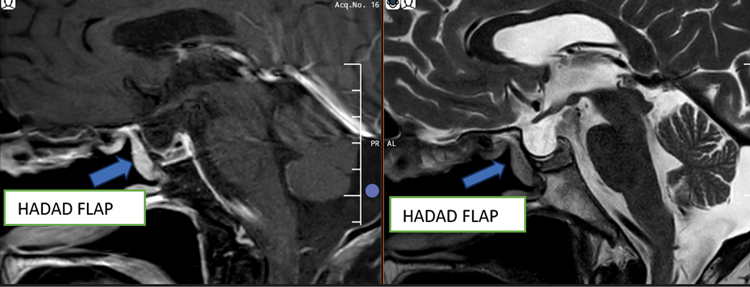

At 6 months, 50 patients had successful defect closure (100%), with no cases of brain herniation and compression of adjacent structures (Table 3 & Figure 6).

Figure 6. MRI AT 6 MONTHS

Conclusion

Endoscopic skull base defect closure demonstrates excellent clinical and radiological outcomes, with no postoperative CSF leaks or infections observed. Most cases of crusting and nasal bleeding resolved within 6 months. In case of decrease in visual acuity post op skull base reconstruction,urgent imaging and reexploration should be done in case of optic nerve compression.In case of recurrent pituitary adenoma, flap can be reused if viable. The employed repair technique is both safe and effective for the management of benign skull base pathologies.

Discussion

El‐Sayed IH et al in their study -postop leak rates with single layer repair was 15.2% and multilayer repair was 1.4%.Thorp BD, Sreenath SB, Ebert CS, Zanation AM in their study 5.3% cases of prolonged skull base crusting. In our study of multilayered closure of skull base defect we had no postoperative CSF leaks or brain herniation.There was crusting in our cases for which saline nasal sprays was used and crusting decreased to 14% by 6 months.In three out of 4 cases of recurrent pituitary adenoma, pedicle was narrow and flap viability was checked with ICG angiography, hadad flap was viable and was reused.

END NOTE

Author information

- Dr Rajesh Raju George, Senior Consultant & HOD, Rajagiri Hospital, Aluva, Kerala.

Email: Rajeshrajugeorge@gmail.com - Dr Sebil Mathai, Fellow in Rhinology,

Rajagiri hospital, Aluva

Email: sebilmathaithekkan@gmail.com - Ms Gayathri Raju, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Rajagiri Hospital, Aluva

Email: gayathriraju00@gmail.com

Financial Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- Rangel-Castilla L, Russin JJ, Spetzler RF. Surgical management of skull base tumors. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;21(4):325–35.

[PubMed] - Kasemsiri P, Carrau RL, Ditzel Filho LFS, Prevedello DM, Otto BA, Old M, De Lara D, Kassam AB. Advantages and limitations of endoscopic endonasal approaches to the skull base. World Neurosurg. 2014 Dec;82(6 Suppl):S12–21.

[Crossref] - De Lara D, Ditzel Filho LF, Prevedello DM, Carrau RL, Kasemsiri P, Otto BA, Kassam AB. Endonasal endoscopic approaches to the paramedian skull base. World neurosurgery. 2014 Dec 1;82(6): S121-9.

- Cavallo LM, Messina A, Cappabianca P, Esposito F, de Divitiis E, Gardner P, Tschabitscher M. Endoscopic endonasal surgery of the midline skull base: anatomical study and clinical considerations. Neurosurgical focus. 2005 Jul 1;19(1):1-4.

- Kassam AB, Prevedello DM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Thomas A, Gardner P, Zanation A, Duz B, Stefko ST, Byers K, Horowitz MB. Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: analysis of complications in the authors’ initial 800 patients: a review. J Neurosurg. 2011 Jun;114(6):1544–68.

[Crossref] - Thorp BD, Sreenath SB, Ebert CS, Zanation AM. Endoscopic skull base reconstruction: a review and clinical case series of 152 vascularized flaps used for surgical skull base defects in the setting of intraoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak. Neurosurgical focus. 2014 Oct 1;37(4):E4.

- Singh CV, Shah NJ. Hadad-Bassagasteguy flap in reconstruction of skull base defects after endonasal skull base surgery. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Oct;3(4):1020-6.

- Hadad G, Bassagasteguy L, Carrau RL, Mataza JC, Kassam A, Snyderman CH, Mintz A. A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: vascular pedicle nasoseptal flap. Laryngoscope. 2006 Oct;116(10):1882–6.

[Crossref] - ElSayed IH, Jiam NT, Theodosopoulos PV, McDermott MW, Gurrola JG, Aghi MK. Formal closure of endoscopic endonasal skull base defects with a “Bow Tie” tri-layer graft. Laryngoscope. 2023 Jul;133(7):1568–75.

[PubMed]